A TOXIN which makes pigs vomit is the surprising key which may have unlocked the century-old mystery of the origins of a Martian meteorite.

In 1931, an unusual stone stored in the geological collection of Purdue University in the USA was identified as a pristine example of a meteorite.

Just how and when the meteorite – which came to be known as Lafayette – ended up in Purdue’s collection has remained unclear for more than 90 years.

One potential origin story, reported by American meteorite collector Harvey Nininger in 1935, is that a Black student at Purdue University witnessed it land in a pond where he was fishing.

Previous attempts to confirm this tale have been inconclusive.

But now, a team of Scots science sleuths have used analysis techniques and archive research to collect enough evidence to suggest that this story is true, and that it happened in either 1919 or 1927.

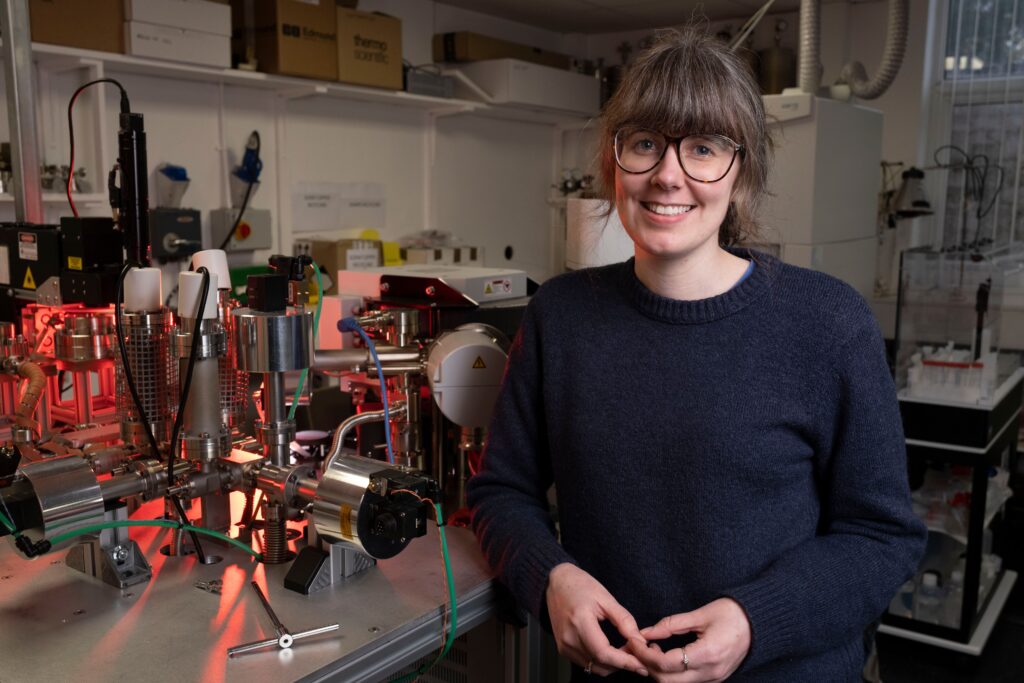

The unravelling of the mystery began in 2019, when planetary scientist Dr Áine O’Brien, of the University of Glasgow’s School of Geographical & Earth Sciences, crushed a tiny sample of Lafayette and used sophisticated mass spectrometry to analyse its composition.

She was looking to discover new details about the presence of organic molecules preserved in Lafayette – evidence which could help us learn more about the possibility of life on Mars.

Among the thousands of metabolites revealed by the analysis, Dr O’Brien noticed an unusually earthbound one – deoxynivalenol, or DON.

DON is a ‘vomitoxin’ found in F. graminearum, a fungus which contaminates grain crops like corn, wheat and oats.

It causes sickness in humans and animals when ingested, with pigs being particularly badly affected.

Dr O’Brien mentioned it to colleagues who were familiar with the story of Lafayette’s muddy touchdown.

They suggested that dust from crops in neighbouring farmland could have carried DON to surrounding waterways, and that Lafayette might have been contaminated by it when the meteorite landed in a pond.

Dr O’Brien turned to researchers at Purdue University’s Department of Agronomy and Department of Botany and Plant Pathology to find out more about the historic prevalence of the fungus in Tippecanoe County in Indiana, where Purdue is located.

Their records showed that it caused a 10-15% drop in crop yield in 1919, and another less pronounced drop in 1927.

With higher prevalence of the fungus comes a greater likelihood that it would be carried beyond the boundaries of farmland.

Analysis of fireball sightings over the same period provided more potential clues to the timing of Lafayette’s landing.

There were reported sightings of a fireball across southern Michigan and northern Indiana on November 26, 1919, and one in 1927 which dropped the Tilden meteorite in Illinois.

Archivists at Purdue University also looked at yearbooks from 1919 and 1927 to find Black students enrolled at the time.

Julius Lee Morgan and Clinton Edward Shaw, of the class of 1921, and Hermanze Edwin Fauntleroy, of the class of 1922, were enrolled at Purdue in 1919.

A fourth man, Clyde Silance, was studying at Purdue in 1927. The researchers conclude that it is possible that one of these men found Lafayette.

Dr O’Brien the paper’s lead author said: “Lafayette is a truly beautiful meteorite sample, which has taught us a lot about Mars through previous research.

“Part of what has made it so valuable is that it’s remarkably well-preserved, which means it must have been recovered quickly after it landed, as Lafayette’s origin story suggested.

“The unusual combination of Lafayette’s swift protection from the elements and the tiny trace of contamination which it picked up during its brief time in the mud is what made this work possible.

“I’m proud that, a century after it reached Earth, we’re finally able to reconstruct the circumstances of its landing and get closer than we’ve ever been to giving credit to the Black student who found it.”

The team’s paper, titled Using Organic Contaminants to Constrain the Terrestrial Journey of the Martian Meteorite Lafayette, is published in Astrobiology.

Researchers from the University of Glasgow’s School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, Purdue University, Carnegie Science, the University of Sydney, the University of Oxford, Monash University, Glasgow Caledonian University and the University of Pavia contributed to the paper.

The research was supported by funding from the Science and Technologies Facilities Council (STFC), the University of Glasgow, the Royal Astronomical Society, the Geological Society of London, and the Scottish Alliance for Geoscience, Environment and Society.