GAELIC-speaking soldiers were used to fool German intelligence during the First World War, according to new research.

A crack team from the Western Isles was based near the front lines in France and given the job of translating key orders into Gaelic.

Every British Army division was assigned a gaelic-speaker who took the messages from HQ and translated them back into English.

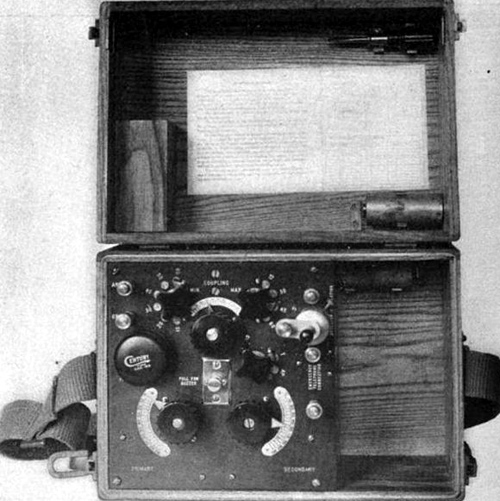

The system meant that, from April 1 1917, orders could securely be broadcast using the latest wireless technology.

The speed of transmission gave the allies an edge over the “Hunnach” in several battles.

A phrase such as “‘That trench is the first line of defence” became utterly incomprehensible to Teutonic ears as “tha an trainnse ud na gàrradh-crìche” while “machine gun post” became “stèisean beairt-ghunna”

At first, eavesdropping German soldiers thought the enemy had simply gone mad under shellfire. Another theory was that British radio operators had been affected by poison gas.

According to Prof Murdo Macleod, who uncovered the amazing story of Operation Guga, the Germans did not realise what the allies were up to until late in 1917.

A diary entry by an oberleutnant of Bavarian Reserve Regiment 104, in trenches facing the Ypres salient in August 1917, makes clear their bafflement.

“Heard those damned Tommies hawking away like mad in their infernal secret language over the radio,” he wrote. “And they have the cheek to claim that German sounds less than euphonious.”

Another remarkable aspect of the story, according to Prof Macleod, is that German intelligence responded by opening a top secret Gaelic school – An Giblean amad – in the Prussian town of Austricksen.

A German who had worked as a waiter in Stornoway and learned the basics of the language was given the near-impossible task of teaching it to German intelligence officers.

The results were so patchy that, in desperation, General der Infanterie Erich Georg Anton von Falkenhayn, at the time the Chief of the General Staff of the German Army, ordered Operation Schottish Winden.

Three of the best students were to land in Scotland by U-boat with the brief of posing as crofters and improving their gaelic to the point where they could crack allied messages.

Unfortunately for the trio, a mix-up meant they were dropped off by not on Lewis but on Skye, where a different version of gaelic is spoken. The three were quickly unmasked as spies and shot.

Little is known about the members of the team who operated from General Haig’s HQ at Château de Beaurepaire in Montreuil-sur-Mer.

But Haig quickly realised the enormous strategic advantage their work gave him and made sure the gaelic team received everything they needed.

Haig did, however, draw the line at a demand for bilingual signs throughout the chateau and its grounds.